Snowpipe Streaming Deep Dive

Disclaimer

The analysis in this blog is based on snowflake-ingest-java version 2.0.5. Anything described in this blog is a result of reverse engineering the SDK, and is likely to change over time as the driver matures and evolves. We will already see a sneak peak and discuss some of the changes made from earlier versions of the SDK.

Introduction

In this blog post, we are going to dive into the implementation details of Snowpipe Streaming. Snowpipe Streaming, as of the day of writing, supports two primary modes:

- Java SDK

- Kafka with Kafka Connect

We are going to go through an in depth analysis of the Java SDK only. We’ll see interesting bits and dive very deep into the magic behind the scenes, and understand how the SDK is built from top to bottom.

Glossary

- Snowpipe Streaming: A feature created by Snowflake to support streaming writes to underlying Snowflake tables. Before this feature, one could use file based Snowpipe, which requires creating a pipe object in Snowflake, putting files in object storage and loading them using the pipe, or alternatively load data via a direct COPY INTO command running on a warehouse

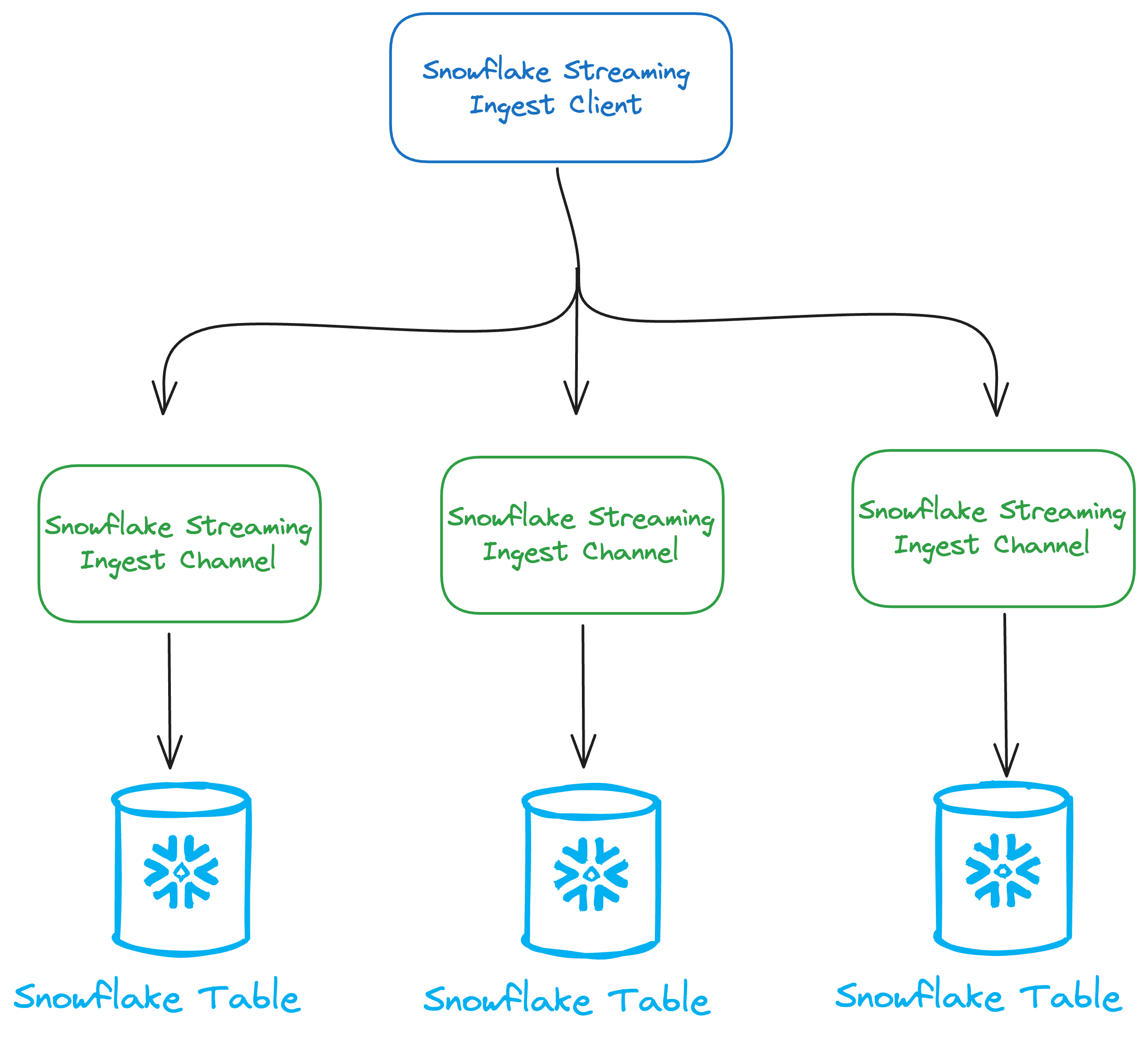

- Snowflake Streaming Client: Entry point of the Java SDK. We use a client to generate 1 to N channels

- Snowflake Streaming Ingest Channel: A channel is an abstraction for writing rows into Snowflake. It’s primary function is the

insertRowandinsertRowsmethods, used for writing a single row or a batch rows, respectively - Apache Arrow: defines a language-independent columnar memory format for flat and hierarchical data, organized for efficient analytic operations on modern hardware like CPUs and GPUs. The Arrow memory format also supports zero-copy reads for lightning-fast data access without serialization overhead

- Apache Parquet: open source, column-oriented data file format designed for efficient data storage and retrieval. It provides efficient data compression and encoding schemes with enhanced performance to handle complex data in bulk.

- SDK: Software Development Kit, a set of platform-specific building tools for developers.

High Level Design

At it’s core, Snowpipe Streaming introduces us to two basic concepts:

Client

Entry point to the SDK. We create a client as a gateway to generating channels.

We create a client using the following builder pattern, providing the essential details to allow for a Snowflake connection:

Properties props = new Properties();

props.put("user", "<user>");

props.put("scheme", "https");

props.put("host", "<orgname>-<account_identifier>.snowflakecomputing.com");

props.put("port", 443);

props.put("role", "<role>");

props.put("private_key", "<private_key>");

SnowflakeStreamingIngestClient client =

SnowflakeStreamingIngestClientFactory

.builder("<my-client-name>")

.setProperties(props)

.build();

Channels

Channels are the means of writing data to Snowflake. Each channel holds a buffer for data which will eventually ship to the designated Snowflake table. You can create as many channels as you’d like in order to increase throughput. Assuming we have a simple schema in our table:

- ID:

NUMBER(38, 0) - NAME:

VARCHAR

SnowflakeStreamingIngestChannel streamingChannel = client.openChannel(

OpenChannelRequest.builder("<my-channel-name>")

.setDBName("<db-name>")

.setSchemaName("<schema-name>")

.setTableName("<table-name>")

.setOnErrorOption(OpenChannelRequest.OnErrorOption.CONTINUE)

.build()

);

HashMap<String, Object> row = new HashMap<>();

row.put("id", 1);

row.put("name", "John");

InsertValidationResponse insertValidationResponse = streamingChannel.insertRow(row, null);

if (insertValidationResponse.hasErrors()) {

System.out.println("Errors: " + String.join(", ", insertValidationResponse

.getInsertErrors()

.stream()

.map(InsertValidationResponse.InsertError::getMessage)

.toArray(String[]::new))

);

}

A channel is a direct connection to a single Snowflake table. Thus, we cannot use a single channel to write to multiple tables. We use the insertRow method to insert a single row of type Map<String, Object>, or we can use insertRows method which receives an Iterable<Map<String, Object>> where we can ship batches of rows together. For each insertion of rows, a client side validation response is returned in the form of InsertValidationResponse, which allows us to monitor for any errors which prevent us from shipping our data.

Diving Deeper

We now understand the mechanism in general: we create a client and a set of channels and use these to communicate with Snowflake tables. This is great at a high level, but there are a few interesting open questions for us to discover:

- What happens with our data once the method returns? Does the response indicate the data has been already stored in Snowflake safely?

- How does the data actually travel from the client to Snowflake?

- What format is being used to ship our data? Are there any interesting optimizations we can learn about Snowflake by the way data is being sent?

- Where is this data being stored? Does it ship directly to native Snowflake tables? Are there any stops along the way?

Let’s unpack all the magic behind the scenes.

From insertRow(s) to Snowflake table

The abstraction is pretty straightforward: we create a client, get ahold of some channels, write the data and BOOM, data is available for querying. Well, yes! BUT, it’s actually a bit more complicated than that :) Let’s see how a table with data being ingested with Snowpipe Streaming is actually built under the hood:

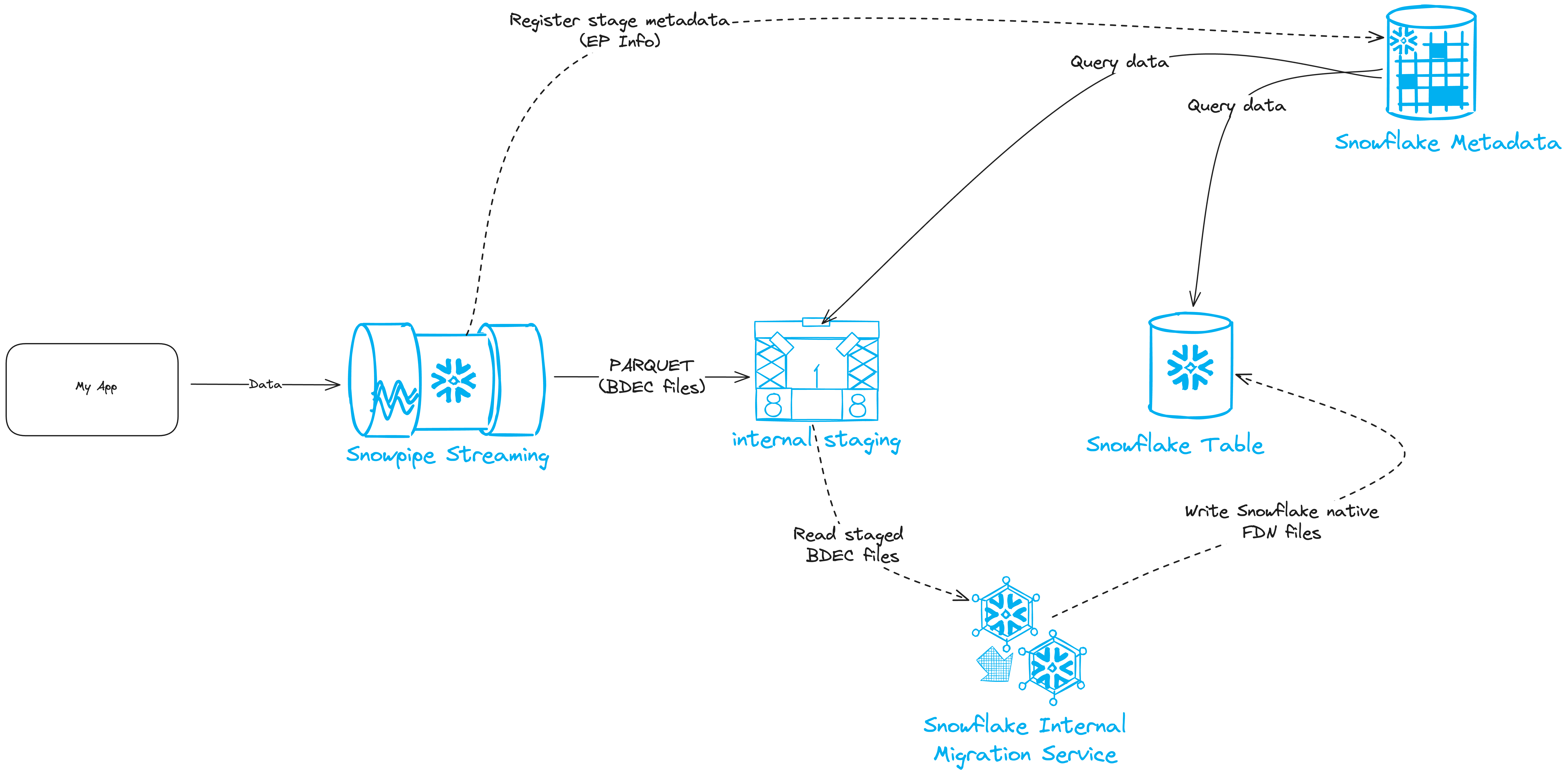

We start with our app, which processes data from various sources we wish to ingest. We spin up the Snowpipe Streaming client, create channels, and start sending data using insertRow(s). Internally, the SDK will take these rows, write them to an internal stage generated by Snowflakes server side and set the path in a class called StreamingIngestStage within the FlushService upon initialization so it knows where it’s destination cloud storage is. Then, files will get written to the internal stage in PARQUET format with an extension called BDEC (Snowflake specific). Once data reaches the internal stage, the client will register it with Snowflakes metadata service so it is queryable by users. In addition to the actual registration of BDEC files, the metadata information on the files written to the stage get sent to Snowflake server side as well. This metadata contains statistics Snowflake calls “EP”s, which Snowflake uses to optimize query execution. Upon every interval (determined by Snowflake), Snowflakes internal migration service will run, consume the BDEC files written since the last execution, store them in Snowflake native format called FDN, and deprecate the PARQUET files in the internal stage.

While data is being streamed to the table, Snowflakes metadata service will know how to generate micro-partitions paths for both the internal stage AND the native table who’s storage location is independent, such that fresh data being written to internal stages is always queryable.

Snowflake & PARQUET? Oh My!

I attended Snowflakes conference here in Israel last year (and even gave a talk!) where they discussed the internal implementation of Snowpipe Streaming. Originally, the chosen file format for storing data was Apache Arrow, which is an in-memory columnar file format used to efficiently transfer data between software components while avoiding the overhead of SerDe (serialization / deserialization) at the software boundaries. This came as a surprise to me, as the data was being streamed and stored directly in cloud storage, so the choice of Arrow seemed peculiar at the time. Anyway, if we take a look at the history of releases for the SDK, we can see Arrow there as well under v1.0.2-beta.2:

- [Improvement] Improve the README and EXAMPLE for Snowpipe Streaming

- [Improvement] Upgrade Apache Arrow library to the latest version

And then we can see somewhere around version v1.0.2-beta.6 (about 5 months later) the transition to Parquet:

v1.0.2-beta.6 Pre-release This release contains a few bug fixes and improvements for Snowpipe Streaming:

- [Improvement] Add parquet file support, this will be our default file format in the future

Converting to Parquet format definitely makes sense, especially when we expect to run queries immediately on fresh data within these tables. Along with the collected EP information within the SDK, we could potentially get close-to-native performance, but the purpose of this post is not to dive in to performance (perhaps a follow up blog :))

Diving into Internal SDK Processing

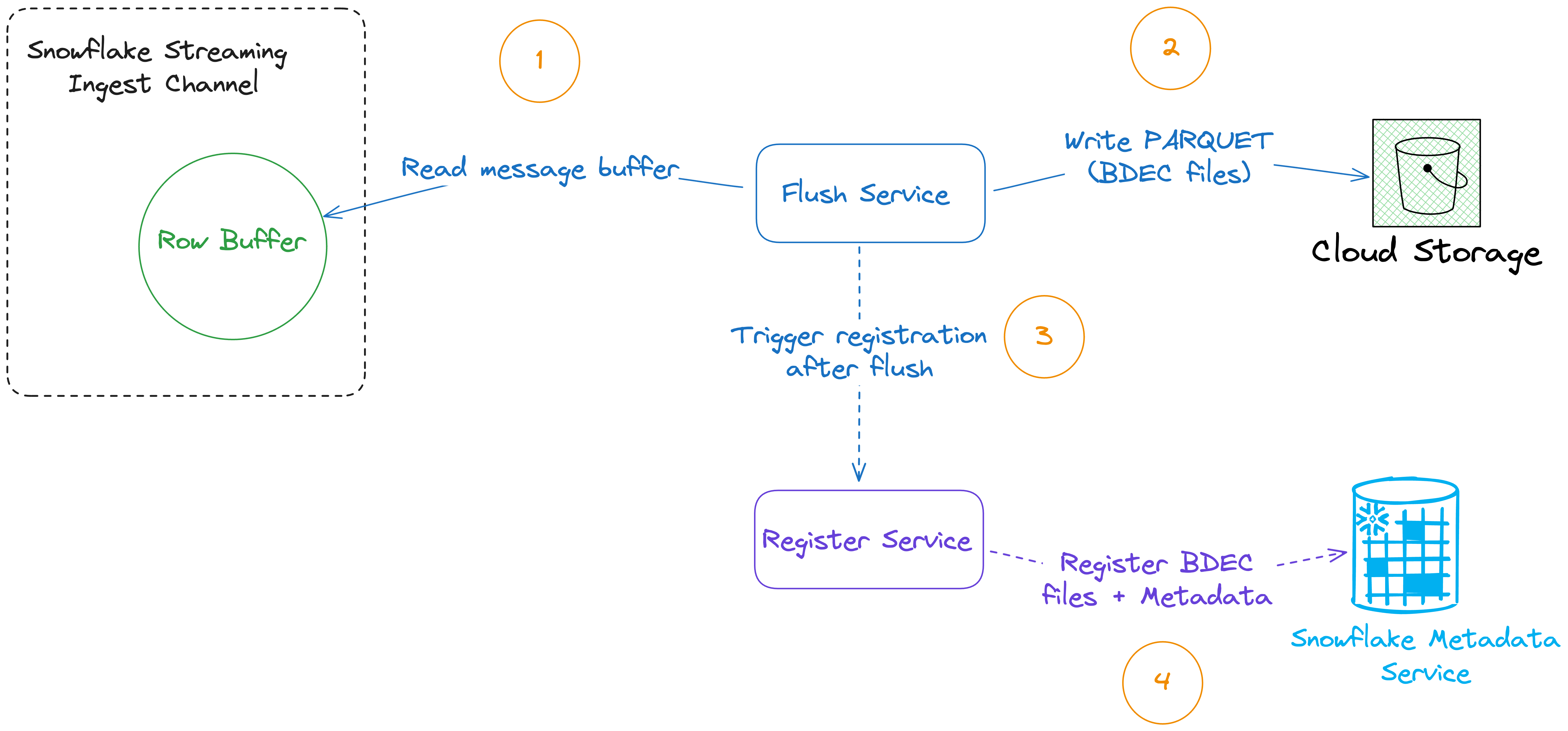

Now that we have the general overview of how data gets written to Snowflake, we can dive a bit further into each internal component, it’s responsibility in the process and all components come together. Let’s take a look at a diagram of how data flows through the SDK:

- Every row that gets written using

insertRow(s)gets written into an internal buffer held by the channel. This buffer is used for storing each one of the batches written to the channel in-memory. - When triggered, the

FlushService<T>reads the data off the row buffer residing within each ingest channel. This happens every predefined interval (which can be configured) defaulting to 1 second. Once data is read, it is serialized to Parquet format, using an extension Snowflake callsBDECand is shipped to the selected stage within the cloud environment your Snowflake instance is running on (Azure, AWS, GCP) - Once data is persisted to cloud storage, next step is to trigger the

RegisterService<T>. This registration service registers the previously written BDEC files along with the chunk metadata information that was collected for each file (we’ll see shortly how this is performed)

Channels & Row Buffers

Alright, let’s start seeing some code. First we’ll explore the concrete implementation for channels: SnowflakeStreamingIngestChannelInternal<T>. This is the implementation that holds the insertRow(s) methods that capture the data we want to transfer to Snowflake. Peeking in, there’s interesting members defined on the class (this is not a full description of all members, only ones I think are interesting):

// Reference to the row buffer

private final RowBuffer<T> rowBuffer;

First and foremost, the RowBuffer<T> is the object instance holding our buffered data. It has two deriving implementations: AbstractRowBuffer<T>, an abstract base class containing default implementations of various methods, and a concrete implementing class:

public class ParquetRowBuffer extends AbstractRowBuffer<ParquetChunkData> {

/* Unflushed rows as Java objects. Needed for the Parquet w/o memory optimization. */

private final List<List<Object>> data;

/* BDEC Parquet writer. It is used to buffer unflushed data in Parquet internal buffers instead of using Java objects */

private BdecParquetWriter bdecParquetWriter;

}

Interesting! the comment suggests that there are actually two underlying buffers here, one for plain Java objects without “Parquet memory optimization” and the second one is within the BdecParquetWriter, said to hold data already in Parquet format. This means that Snowflake is thinking about making the internal buffers more efficient by storing them already in serialized form upon insertion. This option, however, seemed to be currently experimental and turned off by default:

/* Parameter that enables using internal Parquet buffers for buffering of rows before serializing.

It reduces memory consumption compared to using Java Objects for buffering.*/

public static final boolean ENABLE_PARQUET_INTERNAL_BUFFERING_DEFAULT = false;

We then see the decision being made on how to write the row internally based on the nullability of the bdecParquetWriter (this method is within ParquetRowBuffer)

void writeRow(List<Object> row) {

if (clientBufferParameters.getEnableParquetInternalBuffering()) {

bdecParquetWriter.writeRow(row);

} else {

data.add(row);

}

}

Two more interesting fields within the channel definition:

// State of the channel that will be shared with its underlying buffer

private final ChannelRuntimeState channelState;

// Internal map of column name -> column properties

private final Map<String, ColumnProperties> tableColumns;

ChannelRuntimeState is responsible for capturing the internal state of our channel. It holds the offsetToken of our channel, which is akin to a Kafka offset being assigned to every message sent to the server side. It is being incremented and stored during flushing of rows from the internal buffer to Snowflake.

The tableColumns property holds the description of our table schema. It is initialized during the bootstrapping of the channel via the response object sent from the Snowflakes server side to the client in order to register the channel:

@Override

public void setupSchema(List<ColumnMetadata> columns) {

List<Type> parquetTypes = new ArrayList<>();

int id = 1;

for (ColumnMetadata column : columns) {

validateColumnCollation(column);

ParquetTypeGenerator.ParquetTypeInfo typeInfo =

ParquetTypeGenerator.generateColumnParquetTypeInfo(column, id);

parquetTypes.add(typeInfo.getParquetType());

this.metadata.putAll(typeInfo.getMetadata());

int columnIndex = parquetTypes.size() - 1;

fieldIndex.put(

column.getInternalName(),

new ParquetColumn(column, columnIndex, typeInfo.getPrimitiveTypeName()));

if (!column.getNullable()) {

addNonNullableFieldName(column.getInternalName());

}

this.statsMap.put(

column.getInternalName(), new RowBufferStats(column.getName(), column.getCollation()));

if (onErrorOption == OpenChannelRequest.OnErrorOption.ABORT

|| onErrorOption == OpenChannelRequest.OnErrorOption.SKIP_BATCH) {

this.tempStatsMap.put(

column.getInternalName(), new RowBufferStats(column.getName(), column.getCollation()));

}

id++;

}

schema = new MessageType(PARQUET_MESSAGE_TYPE_NAME, parquetTypes);

createFileWriter();

tempData.clear();

data.clear();

}

Note that the schema is being initialized in Parquet schema format, and not with Snowflakes internal schema format. What’s also interesting is that we can take a peek at the internal Snowflake physical file format:

enum ColumnPhysicalType {

ROWINDEX(9),

DOUBLE(7),

SB1(1),

SB2(2),

SB4(3),

SB8(4),

SB16(5),

LOB(8),

BINARY,

ROW(10)

;

}

We can reverse engineer some of the types to try to infer their meaning:

- SB: might stand for “Significant Bit”. We have values 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 bytes, each meant to hold data types of different lengths

- SB1 is used for the BOOLEAN type

- SB4 is used for the DATE type

- SB8 is used for the TIME type

- SB16 is used for the TIMESTAMP type

- LOB: might stand for “Large Object”, I assume this would be a type like STRING

- ROWINDEX: might refer to something related to Snowflake Hybrid Tables?

- DOUBLE: used for FLOAT/DOUBLE type precision objects

Let’s get to the main flow. Let’s see what the code for insertRows looks like:

/**

* Each row is represented using Map where the key is column name and the value is a row of data

*

* @param rows object data to write

* @param offsetToken offset of last row in the row-set, used for replay in case of failures

* @return insert response that possibly contains errors because of insertion failures

* @throws SFException when the channel is invalid or closed

*/

@Override

public InsertValidationResponse insertRows(

Iterable<Map<String, Object>> rows, String offsetToken) {

throttleInsertIfNeeded(new MemoryInfoProviderFromRuntime());

checkValidation();

if (isClosed()) {

throw new SFException(ErrorCode.CLOSED_CHANNEL, getFullyQualifiedName());

}

// We create a shallow copy to protect against concurrent addition/removal of columns, which can

// lead to double counting of null values, for example. Individual mutable values may still be

// concurrently modified (e.g. byte[]). Before validation and EP calculation, we must make sure

// that defensive copies of all mutable objects are created.

final List<Map<String, Object>> rowsCopy = new LinkedList<>();

rows.forEach(r -> rowsCopy.add(new LinkedHashMap<>(r)));

InsertValidationResponse response = this.rowBuffer.insertRows(rowsCopy, offsetToken);

// Start flush task if the chunk size reaches a certain size

// TODO: Checking table/chunk level size reduces throughput a lot, we may want to check it only

// if a large number of rows are inserted

if (this.rowBuffer.getSize()

>= this.owningClient.getParameterProvider().getMaxChannelSizeInBytes()) {

this.owningClient.setNeedFlush();

}

return response;

}

Whenever we ship an Iterable<Map<String, Object>>, it ultimately goes into the rowBuffer object. We get back an InsertValidationResponse, which tells us if there were any errors during the insertion process. Note: this does not send us back validation from Snowflake server side, this is merely a client side validation. Once data is in the buffer, the channel checks to see if we’ve crossed the threshold of max size, and if so it marks this channel for flushing:

/**

* Insert a batch of rows into the row buffer

*

* @param rows input row

* @param offsetToken offset token of the latest row in the batch

* @return insert response that possibly contains errors because of insertion failures

*/

@Override

public InsertValidationResponse insertRows(

Iterable<Map<String, Object>> rows, String offsetToken) {

if (!hasColumns()) {

throw new SFException(ErrorCode.INTERNAL_ERROR, "Empty column fields");

}

InsertValidationResponse response = null;

this.flushLock.lock();

try {

this.channelState.updateInsertStats(System.currentTimeMillis(), this.bufferedRowCount);

IngestionStrategy<T> ingestionStrategy = createIngestionStrategy(onErrorOption);

response = ingestionStrategy.insertRows(this, rows, offsetToken);

} finally {

this.tempStatsMap.values().forEach(RowBufferStats::reset);

clearTempRows();

this.flushLock.unlock();

}

return response;

}

Two interesting things to witness:

- We take a lock on the row buffer, so no concurrent updates happen to the same channel, allowing for internal ordering within a single channel.

-

The concrete implementation of

insertRowsdepends on theIngestionStrategy<T>interface. If you recall, during initialization of the channel, we passed the following property to the channel builder:.setOnErrorOption(OpenChannelRequest.OnErrorOption.CONTINUE)which indicates we want to continue sending data in case the a single row fails to be shipped. Internally, the SDK will initialize a different strategy for the way rows are inserted into the buffer, depending on what we choose.

These are the current strategies that exist within createIngestionStrategy:

/** Create the ingestion strategy based on the channel on_error option */

IngestionStrategy<T> createIngestionStrategy(OpenChannelRequest.OnErrorOption onErrorOption) {

switch (onErrorOption) {

case CONTINUE:

return new ContinueIngestionStrategy<>();

case ABORT:

return new AbortIngestionStrategy<>();

case SKIP_BATCH:

return new SkipBatchIngestionStrategy<>();

default:

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Unknown on error option: " + onErrorOption);

}

}

Let’s analyze the difference between two of them, the continue and abort strategies:

Continue Strategy:

/** Insert rows function strategy for ON_ERROR=CONTINUE */

public class ContinueIngestionStrategy<T> implements IngestionStrategy<T> {

@Override

public InsertValidationResponse insertRows(

AbstractRowBuffer<T> rowBuffer, Iterable<Map<String, Object>> rows, String offsetToken) {

InsertValidationResponse response = new InsertValidationResponse();

float rowsSizeInBytes = 0F;

int rowIndex = 0;

for (Map<String, Object> row : rows) {

InsertValidationResponse.InsertError error =

new InsertValidationResponse.InsertError(row, rowIndex);

try {

if (rowBuffer.bufferedRowCount == Integer.MAX_VALUE) {

throw new SFException(ErrorCode.INTERNAL_ERROR, "Row count reaches MAX value");

}

Set<String> inputColumnNames = verifyInputColumns(row, error, rowIndex);

rowsSizeInBytes +=

addRow(

row, rowBuffer.bufferedRowCount, rowBuffer.statsMap, inputColumnNames, rowIndex);

rowBuffer.bufferedRowCount++;

} catch (SFException e) {

error.setException(e);

response.addError(error);

} catch (Throwable e) {

logger.logWarn("Unexpected error happens during insertRows: {}", e);

error.setException(new SFException(e, ErrorCode.INTERNAL_ERROR, e.getMessage()));

response.addError(error);

}

rowIndex++;

}

checkBatchSizeRecommendedMaximum(rowsSizeInBytes);

rowBuffer.channelState.setOffsetToken(offsetToken);

rowBuffer.bufferSize += rowsSizeInBytes;

rowBuffer.rowSizeMetric.accept(rowsSizeInBytes);

return response;

}

}

Abort Strategy:

/** Insert rows function strategy for ON_ERROR=ABORT */

public class AbortIngestionStrategy<T> implements IngestionStrategy<T> {

@Override

public InsertValidationResponse insertRows(

AbstractRowBuffer<T> rowBuffer, Iterable<Map<String, Object>> rows, String offsetToken) {

// If the on_error option is ABORT, simply throw the first exception

InsertValidationResponse response = new InsertValidationResponse();

float rowsSizeInBytes = 0F;

float tempRowsSizeInBytes = 0F;

int tempRowCount = 0;

for (Map<String, Object> row : rows) {

Set<String> inputColumnNames = verifyInputColumns(row, null, tempRowCount);

tempRowsSizeInBytes +=

addTempRow(row, tempRowCount, rowBuffer.tempStatsMap, inputColumnNames, tempRowCount);

tempRowCount++;

checkBatchSizeEnforcedMaximum(tempRowsSizeInBytes);

if ((long) rowBuffer.bufferedRowCount + tempRowCount >= Integer.MAX_VALUE) {

throw new SFException(ErrorCode.INTERNAL_ERROR, "Row count reaches MAX value");

}

}

checkBatchSizeRecommendedMaximum(tempRowsSizeInBytes);

moveTempRowsToActualBuffer(tempRowCount);

rowsSizeInBytes = tempRowsSizeInBytes;

rowBuffer.bufferedRowCount += tempRowCount;

rowBuffer.statsMap.forEach(

(colName, stats) ->

rowBuffer.statsMap.put(

colName,

RowBufferStats.getCombinedStats(stats, rowBuffer.tempStatsMap.get(colName))));

rowBuffer.channelState.setOffsetToken(offsetToken);

rowBuffer.bufferSize += rowsSizeInBytes;

rowBuffer.rowSizeMetric.accept(rowsSizeInBytes);

return response;

}

}

The main difference between these two strategies is that for continue, we add data directly to the data buffer in the channel. For the abort strategy, we first hold a tempBuffer along with temporary statistics and only write in case the happy flow for the method falls through. Otherwise an exception is thrown that gets caught in the parent insertRows method cleaning up the temp buffer during finalization:

} finally {

this.tempStatsMap.values().forEach(RowBufferStats::reset);

clearTempRows();

this.flushLock.unlock();

}

Parsing Java Objects to Parquet and Statistics Collection

Regardless of which strategy is used, both implementations end up calling ParquetRowBuffer.addRow where the parsing from JVM object to Parquet and collecting statistics happens. Before we dive in to how adding rows works, let’s see how the statistics get collected. For each object, we collect a RowBufferStats object, which looks like this:

class RowBufferStats {

private byte[] currentMinStrValue;

private byte[] currentMaxStrValue;

private BigInteger currentMinIntValue;

private BigInteger currentMaxIntValue;

private Double currentMinRealValue;

private Double currentMaxRealValue;

private long currentNullCount;

// for binary or string columns

private long currentMaxLength;

}

During the processing, we see the following range values collected:

- Min/Max String Value

- Min/Max Int Value

- Min/Max Real Value

- Null Count

- Max String/Binary Length

These statistics, collected on a per object basis, are then combined at the batch level when the data is flushed using getCombinedStats:

static RowBufferStats getCombinedStats(RowBufferStats left, RowBufferStats right) {

RowBufferStats combined =

new RowBufferStats(left.columnDisplayName, left.getCollationDefinitionString());

if (left.currentMinIntValue != null) {

combined.addIntValue(left.currentMinIntValue);

combined.addIntValue(left.currentMaxIntValue);

}

if (right.currentMinIntValue != null) {

combined.addIntValue(right.currentMinIntValue);

combined.addIntValue(right.currentMaxIntValue);

}

if (left.currentMinStrValue != null) {

combined.addBinaryValue(left.currentMinStrValue);

combined.addBinaryValue(left.currentMaxStrValue);

}

if (right.currentMinStrValue != null) {

combined.addBinaryValue(right.currentMinStrValue);

combined.addBinaryValue(right.currentMaxStrValue);

}

if (left.currentMinRealValue != null) {

combined.addRealValue(left.currentMinRealValue);

combined.addRealValue(left.currentMaxRealValue);

}

if (right.currentMinRealValue != null) {

combined.addRealValue(right.currentMinRealValue);

combined.addRealValue(right.currentMaxRealValue);

}

combined.currentNullCount = left.currentNullCount + right.currentNullCount;

combined.currentMaxLength = Math.max(left.currentMaxLength, right.currentMaxLength);

return combined;

}

Thus, we end up aggregating all the stats across all values of a given column. Armed with statistics collection understanding.

Having looked at statistics collection, lets now see how addRows does the processing of rows:

private float addRow(

Map<String, Object> row,

Consumer<List<Object>> out,

Map<String, RowBufferStats> statsMap,

Set<String> inputColumnNames,

long insertRowsCurrIndex) {

Object[] indexedRow = new Object[fieldIndex.size()];

float size = 0F;

// Create new empty stats just for the current row.

Map<String, RowBufferStats> forkedStatsMap = new HashMap<>();

for (Map.Entry<String, Object> entry : row.entrySet()) {

String key = entry.getKey();

Object value = entry.getValue();

String columnName = LiteralQuoteUtils.unquoteColumnName(key);

ParquetColumn parquetColumn = fieldIndex.get(columnName);

int colIndex = parquetColumn.index;

RowBufferStats forkedStats = statsMap.get(columnName).forkEmpty();

forkedStatsMap.put(columnName, forkedStats);

ColumnMetadata column = parquetColumn.columnMetadata;

ParquetValueParser.ParquetBufferValue valueWithSize =

ParquetValueParser.parseColumnValueToParquet(

value, column, parquetColumn.type, forkedStats, defaultTimezone, insertRowsCurrIndex);

indexedRow[colIndex] = valueWithSize.getValue();

size += valueWithSize.getSize();

}

long rowSizeRoundedUp = Double.valueOf(Math.ceil(size)).longValue();

if (rowSizeRoundedUp > clientBufferParameters.getMaxAllowedRowSizeInBytes()) {

throw new SFException(

ErrorCode.MAX_ROW_SIZE_EXCEEDED,

String.format(

"rowSizeInBytes:%.3f, maxAllowedRowSizeInBytes:%d, rowIndex:%d",

size, clientBufferParameters.getMaxAllowedRowSizeInBytes(), insertRowsCurrIndex));

}

out.accept(Arrays.asList(indexedRow));

// All input values passed validation, iterate over the columns again and combine their existing

// statistics with the forked statistics for the current row.

for (Map.Entry<String, RowBufferStats> forkedColStats : forkedStatsMap.entrySet()) {

String columnName = forkedColStats.getKey();

statsMap.put(

columnName,

RowBufferStats.getCombinedStats(statsMap.get(columnName), forkedColStats.getValue()));

}

// Increment null count for column missing in the input map

for (String columnName : Sets.difference(this.fieldIndex.keySet(), inputColumnNames)) {

statsMap.get(columnName).incCurrentNullCount();

}

return size;

}

Since this is an important part of the code, lets go through it step by step:

- Column name & value are retrieved. Using the column name, we extract the field index of the

ParquetColumnwhich is our target format. - Initialize an empty

RowBufferStatsobject, we’ll use it for statistics of the current row. - Call

ParquetValueParser.parseColumnValueToParquetto parse the JVM object into Parquet format & collecting statistics. - Add the row to the underlying data buffer or temporary buffer (depending on the ingestion strategy) using the

outparameter (Consumer<List<Object>>). - Combine the current collected statistics for the column with the previous collected statistics for the batch and update

statsMap - Increment null count for missing columns

- Return the total size of the Parquet converted object

Since the parseColumnValueToParquet method is rather lengthy, I leave this as an exercise for the reader to actually see the details of how values are actually being parsed and stats collected.

Flushing the Data

We’ve got the rows in the internal buffers parsed out in Parquet format and statistics collected. Every interval, controlled by the MAX_CLIENT_LAG parameter, the FlushService<T> will attempt to flush all channels for the given client. Let’s again start by exploring some interesting fields set at the class level

// Reference to the channel cache

private final ChannelCache<T> channelCache;

// Reference to the Streaming Ingest stage

private final StreamingIngestStage targetStage;

// Reference to register service

private final RegisterService<T> registerService;

// blob encoding version

private final Constants.BdecVersion bdecVersion;

ChannelCache<T>holds a reference to all open channels, internally, it maps each fully qualified table name to the selected channel it pushes data to, as a single channel may only emit rows of a single table.StreamingIngestStageholds the cloud storage location the flush service will emit data to, alongside temporary credentials generated by Snowflake server side.RegisterService<T>is responsible for registering the files emitted to the Snowflake stage along with the statistics collected by theParquetRowBufferonce flushing is completeBdecVersionholds the current version of Bdec being currently used.

As I wrote above, previous versions of the feature were based on Arrow rather than Parquet, and this is apparent in the BdecVersion enum:

/** The write mode to generate BDEC file. */

public enum BdecVersion {

// Unused (previously Arrow)

// ONE(1),

// Unused (previously Arrow with per column compression.

// TWO(2),

/**

* Uses Parquet to generate BDEC chunks with {@link

* net.snowflake.ingest.streaming.internal.ParquetRowBuffer} (page-level compression). This

* version is experimental and WIP at the moment.

*/

THREE(3);

}

Great! now let’s look at the FlushService.createWorkers method which is responsible for initializing the background workers for flushing and the dedicated threadpools:

private void createWorkers() {

// Create thread for checking and scheduling flush job

ThreadFactory flushThreadFactory =

new ThreadFactoryBuilder().setNameFormat("ingest-flush-thread").build();

this.flushWorker = Executors.newSingleThreadScheduledExecutor(flushThreadFactory);

this.flushWorker.scheduleWithFixedDelay(

() -> {

flush(false)

.exceptionally(

e -> {

String errorMessage =

String.format(

"Background flush task failed, client=%s, exception=%s, detail=%s,"

+ " trace=%s.",

this.owningClient.getName(),

e.getCause(),

e.getCause().getMessage(),

getStackTrace(e.getCause()));

logger.logError(errorMessage);

if (this.owningClient.getTelemetryService() != null) {

this.owningClient

.getTelemetryService()

.reportClientFailure(this.getClass().getSimpleName(), errorMessage);

}

return null;

});

},

0,

this.owningClient.getParameterProvider().getBufferFlushCheckIntervalInMs(),

TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS);

// Create thread for registering blobs

ThreadFactory registerThreadFactory =

new ThreadFactoryBuilder().setNameFormat("ingest-register-thread").build();

this.registerWorker = Executors.newSingleThreadExecutor(registerThreadFactory);

// Create threads for building and uploading blobs

// Size: number of available processors * (1 + IO time/CPU time)

ThreadFactory buildUploadThreadFactory =

new ThreadFactoryBuilder().setNameFormat("ingest-build-upload-thread-%d").build();

int buildUploadThreadCount =

Math.min(

Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors()

* (1 + this.owningClient.getParameterProvider().getIOTimeCpuRatio()),

MAX_THREAD_COUNT);

this.buildUploadWorkers =

Executors.newFixedThreadPool(buildUploadThreadCount, buildUploadThreadFactory);

logger.logInfo(

"Create {} threads for build/upload blobs for client={}, total available processors={}",

buildUploadThreadCount,

this.owningClient.getName(),

Runtime.getRuntime().availableProcessors());

}

All in all, we have 3 main background workers being spun up:

- “ingest-flush-thread”: will flush data every

getBufferFlushCheckIntervalInMs, which is internally based on theBUFFER_FLUSH_CHECK_INTERVAL_IN_MILLISconstant andBUFFER_FLUSH_CHECK_INTERVAL_IN_MILLIS_DEFAULTdefault which is set to 100 milliseconds. - “ingest-register-thread”: dedicated

ExecutorServiceresponsible for file and registration - “ingest-build-upload-thread”: dedicated

ExecutorServiceresponsible for concurrently uploading blobs to cloud storage. Number of workers are determined by the number of available cores times the IO time ratio plus 1 (default IO time ratio is set to 2 and is determined byIO_TIME_CPU_RATIO_DEFAULT)

Let’s zoom and and analyze the flushing operation call chain:

/**

* Kick off a flush job and distribute the tasks if one of the following conditions is met:

* <li>Flush is forced by the users

* <li>One or more buffers have reached the flush size

* <li>Periodical background flush when a time interval has reached

*

* @param isForce

* @return Completable future that will return when the blobs are registered successfully, or null

* if none of the conditions is met above

*/

CompletableFuture<Void> flush(boolean isForce) {

long timeDiffMillis = System.currentTimeMillis() - this.lastFlushTime;

if (isForce

|| (!DISABLE_BACKGROUND_FLUSH

&& !isTestMode()

&& (this.isNeedFlush

|| timeDiffMillis

>= this.owningClient.getParameterProvider().getCachedMaxClientLagInMs()))) {

return this.statsFuture()

.thenCompose((v) -> this.distributeFlush(isForce, timeDiffMillis))

.thenCompose((v) -> this.registerFuture());

}

return this.statsFuture();

}

There are a two conditions for executing a flush:

The force flag to the flush method was set to true

OR

(We haven’t disabled background flushing AND isNeedFlush flag is set to true) OR the time delta since last execution has crossed the max client lag threshold.

If all conditions are met, we kick off a chain of futures that:

- Register current CPU stats to the histogram maintained by the client

- Flush the data in the channels

- Register the new files with Snowflakes server side

The distributeFlush method internally is pretty lengthy, so I’m picking selected code highlights that matter for understanding the flow of execution.

Iterator<

Map.Entry<

String, ConcurrentHashMap<String, SnowflakeStreamingIngestChannelInternal<T>>>>

itr = this.channelCache.iterator();

List<Pair<BlobData<T>, CompletableFuture<BlobMetadata>>> blobs = new ArrayList<>();

List<ChannelData<T>> leftoverChannelsDataPerTable = new ArrayList<>();

We start out by getting an iterator of all channels, and creating a buffer reference for all executed blob (channel data) futures. We then start to enumerate the channels, getting the path to store for each blob within each channel:

List<List<ChannelData<T>>> blobData = new ArrayList<>();

float totalBufferSizeInBytes = 0F;

final String blobPath = getBlobPath(this.targetStage.getClientPrefix());

We then check to see if the we haven’t reached the maximum allowed chunks in blob + registration requests. If we have, we break the execution and wait until the next flush operation will kick off:

} else if (blobData.size()

>= this.owningClient

.getParameterProvider()

.getMaxChunksInBlobAndRegistrationRequest()) {

// Create a new blob if the current one already contains max allowed number of chunks

logger.logInfo(

"Max allowed number of chunks in the current blob reached. chunkCount={}"

+ " maxChunkCount={} currentBlobPath={}",

blobData.size(),

this.owningClient.getParameterProvider().getMaxChunksInBlobAndRegistrationRequest(),

blobPath);

break;

If we haven’t reached the limit, we kick off a parallel stream that gets the data for each one of the channels:

ConcurrentHashMap<String, SnowflakeStreamingIngestChannelInternal<T>> table =

itr.next().getValue();

// Use parallel stream since getData could be the performance bottleneck when we have a

// high number of channels

table.values().parallelStream()

.forEach(

channel -> {

if (channel.isValid()) {

ChannelData<T> data = channel.getData(blobPath);

if (data != null) {

channelsDataPerTable.add(data);

}

}

});

}

Internally, channel.getData flushes the channels rowBuffer:

/**

* Get all the data needed to build the blob during flush

*

* @param filePath the name of the file the data will be written in

* @return a ChannelData object

*/

ChannelData<T> getData(final String filePath) {

ChannelData<T> data = this.rowBuffer.flush(filePath);

if (data != null) {

data.setChannelContext(channelFlushContext);

}

return data;

}

Once we get all the data, we start to build the chunks. Each chunk being built must:

- Be up to 256 MB in size

- Have the same encryption IDs

- Have the same table schema

All channel data gets added to the blobData field, which is a List<List<ChannelData<T>>>:

blobData.add(channelsDataPerTable.subList(0, idx));

Now that we have the blobData ready, we start building the chunk and uploading to cloud storage:

CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(

() -> {

try {

BlobMetadata blobMetadata = buildAndUpload(blobPath, blobData);

blobMetadata.getBlobStats().setFlushStartMs(flushStartMs);

return blobMetadata;

} catch (Throwable e) {

// Omitted for brevity

}

this.buildUploadWorkers)));

The first step in the process, is to build the blob bytes and metadata. in order perform this, each ChannelData<T> instance keeps it’s own Flusher<T> instance, which knows how to serialize the data according to the channel schema. Internally, the instance being used is a ParquetFlusher:

public class ParquetFlusher implements Flusher<ParquetChunkData>

Next, we take all the statistics collected for each chunk in the channel, and aggregate it into a single statistics object per column:

columnEpStatsMapCombined =

ChannelData.getCombinedColumnStatsMap(columnEpStatsMapCombined, data.getColumnEps());

chunkMinMaxInsertTimeInMs =

ChannelData.getCombinedMinMaxInsertTimeInMs(

chunkMinMaxInsertTimeInMs, data.getMinMaxInsertTimeInMs());

Then, we store all the rows for processing and get the total row count and estimated uncompressed size

rows.addAll(data.getVectors().rows);

rowCount += data.getRowCount();

chunkEstimatedUncompressedSize += data.getBufferSize();

Finally, we create the BdecParquetWriter, which is a Snowflake SDK Parquet writer meant to control some configuration aspects of the serialization process which conform limitations within Snowflakes server side implementation responsible for reading the BDECs:

Map<String, String> metadata = channelsDataPerTable.get(0).getVectors().metadata;

parquetWriter =

new BdecParquetWriter(

mergedData,

schema,

metadata,

firstChannelFullyQualifiedTableName,

maxChunkSizeInBytes,

bdecParquetCompression);

rows.forEach(parquetWriter::writeRow);

parquetWriter.close();

return new SerializationResult(

channelsMetadataList,

columnEpStatsMapCombined,

rowCount,

chunkEstimatedUncompressedSize,

mergedData,

chunkMinMaxInsertTimeInMs);

}

SerializationResult holds all the relevant data stored in the mergedData field which is a ByteArrayOutputStream along with the collected metadata.

Note: if the optimization of storing data in-memory in Parquet format was turned on, the code path would skip the serialization step and take the already built byte[] and put it into the ByteArrayOutputStream directly, skipping the serialization altogether.

Data is ready in serialized form, the next step is to take care of encryption of the data and create the metadata structure for Snowflakes server side. First, the chunked data is being padded to conform to Snowflakes internal encryption standards:

ByteArrayOutputStream chunkData = serializedChunk.chunkData;

Pair<byte[], Integer> paddedChunk =

padChunk(chunkData, Constants.ENCRYPTION_ALGORITHM_BLOCK_SIZE_BYTES);

byte[] paddedChunkData = paddedChunk.getFirst();

int paddedChunkLength = paddedChunk.getSecond();

Then it gets encrypted and a MD5 hash is emitted for checksum:

byte[] encryptedCompressedChunkData =

Cryptor.encrypt(

paddedChunkData, firstChannelFlushContext.getEncryptionKey(), filePath, iv);

// Compute the md5 of the chunk data

String md5 = computeMD5(encryptedCompressedChunkData, paddedChunkLength);

Next, we build the ChunkMetadata object for each chunk in the list:

ChunkMetadata chunkMetadata =

ChunkMetadata.builder()

.setOwningTableFromChannelContext(firstChannelFlushContext)

// The start offset will be updated later in BlobBuilder#build to include the blob

// header

.setChunkStartOffset(startOffset)

// The paddedChunkLength is used because it is the actual data size used for

// decompression and md5 calculation on server side.

.setChunkLength(paddedChunkLength)

.setUncompressedChunkLength((int) serializedChunk.chunkEstimatedUncompressedSize)

.setChannelList(serializedChunk.channelsMetadataList)

.setChunkMD5(md5)

.setEncryptionKeyId(firstChannelFlushContext.getEncryptionKeyId())

.setEpInfo(

AbstractRowBuffer.buildEpInfoFromStats(

serializedChunk.rowCount, serializedChunk.columnEpStatsMapCombined))

.setFirstInsertTimeInMs(serializedChunk.chunkMinMaxInsertTimeInMs.getFirst())

.setLastInsertTimeInMs(serializedChunk.chunkMinMaxInsertTimeInMs.getSecond())

.build();

Note the conversion from RowBufferStats to EpInfo which happens for the metadata. Essentially the former and the latter schema is exactly on par, just introducing additional defaults and validations:

FileColumnProperties(RowBufferStats stats) {

this.setCollation(stats.getCollationDefinitionString());

this.setMaxIntValue(

stats.getCurrentMaxIntValue() == null

? DEFAULT_MIN_MAX_INT_VAL_FOR_EP

: stats.getCurrentMaxIntValue());

this.setMinIntValue(

stats.getCurrentMinIntValue() == null

? DEFAULT_MIN_MAX_INT_VAL_FOR_EP

: stats.getCurrentMinIntValue());

this.setMinRealValue(

stats.getCurrentMinRealValue() == null

? DEFAULT_MIN_MAX_REAL_VAL_FOR_EP

: stats.getCurrentMinRealValue());

this.setMaxRealValue(

stats.getCurrentMaxRealValue() == null

? DEFAULT_MIN_MAX_REAL_VAL_FOR_EP

: stats.getCurrentMaxRealValue());

this.setMaxLength(stats.getCurrentMaxLength());

this.setMaxStrNonCollated(null);

this.setMinStrNonCollated(null);

// current hex-encoded min value, truncated down to 32 bytes

if (stats.getCurrentMinStrValue() != null) {

String truncatedAsHex = truncateBytesAsHex(stats.getCurrentMinStrValue(), false);

this.setMinStrValue(truncatedAsHex);

}

// current hex-encoded max value, truncated up to 32 bytes

if (stats.getCurrentMaxStrValue() != null) {

String truncatedAsHex = truncateBytesAsHex(stats.getCurrentMaxStrValue(), true);

this.setMaxStrValue(truncatedAsHex);

}

this.setNullCount(stats.getCurrentNullCount());

this.setDistinctValues(stats.getDistinctValues());

}

Then, we take the chunk list and the metadata list and form the blob bytes:

// Build blob file bytes

byte[] blobBytes =

buildBlob(chunksMetadataList, chunksDataList, crc.getValue(), curDataSize, bdecVersion);

And for those who like to KNOW IT ALL, here’s the layout being used to store everything within the shipped byte[]:

/**

* Build the blob file bytes

*

* @param chunksMetadataList List of chunk metadata

* @param chunksDataList List of chunk data

* @param chunksChecksum Checksum for the chunk data portion

* @param chunksDataSize Total size for the chunk data portion after compression

* @param bdecVersion BDEC file version

* @return The blob file as a byte array

* @throws JsonProcessingException

*/

static byte[] buildBlob(

List<ChunkMetadata> chunksMetadataList,

List<byte[]> chunksDataList,

long chunksChecksum,

long chunksDataSize,

Constants.BdecVersion bdecVersion)

throws IOException {

byte[] chunkMetadataListInBytes = MAPPER.writeValueAsBytes(chunksMetadataList);

int metadataSize =

BLOB_NO_HEADER

? 0

: BLOB_TAG_SIZE_IN_BYTES

+ BLOB_VERSION_SIZE_IN_BYTES

+ BLOB_FILE_SIZE_SIZE_IN_BYTES

+ BLOB_CHECKSUM_SIZE_IN_BYTES

+ BLOB_CHUNK_METADATA_LENGTH_SIZE_IN_BYTES

+ chunkMetadataListInBytes.length;

// Create the blob file and add the metadata

ByteArrayOutputStream blob = new ByteArrayOutputStream();

if (!BLOB_NO_HEADER) {

blob.write(BLOB_EXTENSION_TYPE.getBytes());

blob.write(bdecVersion.toByte());

blob.write(toByteArray(metadataSize + chunksDataSize));

blob.write(toByteArray(chunksChecksum));

blob.write(toByteArray(chunkMetadataListInBytes.length));

blob.write(chunkMetadataListInBytes);

}

for (byte[] chunkData : chunksDataList) {

blob.write(chunkData);

}

// We need to update the start offset for the EP and Parquet data in the request since

// some metadata was added at the beginning

for (ChunkMetadata chunkMetadata : chunksMetadataList) {

chunkMetadata.advanceStartOffset(metadataSize);

}

return blob.toByteArray();

}

In case BLOB_NO_HEADER is set (it is currently set to true) there is no header being padded to the chunked data. Otherwise, it writes out:

- Tag

- Version

- Total size (metadata + chunk)

- Checksum

- Metadata list

Then, all chunk data is added. If the blob header is written, then the starting offset of the chunk is also advanced to align with the metadata size.

We’re all set!, we can now ship the serialized blob using StreamingIngestStage:

this.targetStage.put(blobPath, blob);

Registering Blobs with Snowflake

The last step in the process is to register the blobs being written to Snowflake using the RegisterService<T>:

// Add the flush task futures to the register service

this.registerService.addBlobs(blobs);

Where blobs is a list of pairs of BlobData<T> and CompletableFuture<BlobMetadata>.

The registration process kicks off with the registerFuture method:

/**

* Registers blobs with Snowflake

*

* @return

*/

private CompletableFuture<Void> registerFuture() {

return CompletableFuture.runAsync(

() -> this.registerService.registerBlobs(latencyTimerContextMap), this.registerWorker);

}

registerBlobs holds the actual interesting bits. Again, as it is a lengthy implementation, I’ll carve out the interesting bits from whats going on.

First, a global lock is taken to unsure the registration does not happen concurrently:

if (this.blobsListLock.tryLock())

Then, the blob upload future is being synchronously waited on with a default timeout:

// Wait for uploading to finish

BlobMetadata blob =

futureBlob.getValue().get(BLOB_UPLOAD_TIMEOUT_IN_SEC, TimeUnit.SECONDS);

Where the current timeout is set to 5 seconds. If the blob has finished, it gets added to a blobs list to be processed later. In case a TimeoutException is thrown, the waiting for the blob will be retried until retry count is exhausted (current default count is 24). If any other exception was thrown or the retry count is exhausted, the channel will be invalidated and the user will need to re-open another one.

this.owningClient

.getFlushService()

.invalidateAllChannelsInBlob(futureBlob.getKey().getData());

errorBlobs.add(futureBlob.getKey());

retry = 0;

idx++;

Assuming blobs completed without errors, we finally move to the registration phase, which is being performed by the owning client of the channel:

// Register the blobs, and invalidate any channels that return a failure status code

this.owningClient.registerBlobs(blobs);

And here’s registerBlobs:

/**

* Register the uploaded blobs to a Snowflake table

*

* @param blobs list of uploaded blobs

* @param executionCount Number of times this call has been attempted, used to track retries

*/

void registerBlobs(List<BlobMetadata> blobs, final int executionCount) {

logger.logInfo(

"Register blob request preparing for blob={}, client={}, executionCount={}",

blobs.stream().map(BlobMetadata::getPath).collect(Collectors.toList()),

this.name,

executionCount);

RegisterBlobResponse response = null;

try {

Map<Object, Object> payload = new HashMap<>();

payload.put(

"request_id", this.flushService.getClientPrefix() + "_" + counter.getAndIncrement());

payload.put("blobs", blobs);

payload.put("role", this.role);

response =

executeWithRetries(

RegisterBlobResponse.class,

REGISTER_BLOB_ENDPOINT,

payload,

"register blob",

STREAMING_REGISTER_BLOB,

httpClient,

requestBuilder);

// Check for Snowflake specific response code

if (response.getStatusCode() != RESPONSE_SUCCESS) {

logger.logDebug(

"Register blob request failed for blob={}, client={}, message={}, executionCount={}",

blobs.stream().map(BlobMetadata::getPath).collect(Collectors.toList()),

this.name,

response.getMessage(),

executionCount);

throw new SFException(ErrorCode.REGISTER_BLOB_FAILURE, response.getMessage());

}

} catch (IOException | IngestResponseException e) {

throw new SFException(e, ErrorCode.REGISTER_BLOB_FAILURE, e.getMessage());

}

The blob metadata, including the EpInfo that was collected, are registered with Snowflakes server side. In case the registration fails, channels will get invalidated and will need to be re-opened. In case the Snowflake queue receiving this metadata information is full, the client will retry up until MAX_STREAMING_INGEST_API_CHANNEL_RETRY, which is currently set to 3:

if (channelStatus.getStatusCode() != RESPONSE_SUCCESS) {

// If the chunk queue is full, we wait and retry the chunks

if ((channelStatus.getStatusCode()

== RESPONSE_ERR_ENQUEUE_TABLE_CHUNK_QUEUE_FULL

|| channelStatus.getStatusCode()

== RESPONSE_ERR_GENERAL_EXCEPTION_RETRY_REQUEST)

&& executionCount

< MAX_STREAMING_INGEST_API_CHANNEL_RETRY) {

queueFullChunks.add(chunkStatus);

Once this method has finished, the files and metadata have being uploaded and registered with Snowflake, available for querying!

Bonus: BdecParquetWriter and Internal Parquet Configuration

There are a few interesting configuration values being set with the writer being used by SDK:

private static ParquetProperties createParquetProperties() {

/**

* There are two main limitations on the server side that we have to overcome by tweaking

* Parquet limits:

*

* <p>1. Scanner supports only the case when the row number in pages is the same. Remember that

* a page has data from only one column.

*

* <p>2. Scanner supports only 1 row group per Parquet file.

*

* <p>We can't guarantee that each page will have the same number of rows, because we have no

* internal control over Parquet lib. That's why to satisfy 1., we will generate one page per

* column.

*

* <p>To satisfy 1. and 2., we will disable a check that decides when to flush buffered rows to

* row groups and pages. The check happens after a configurable amount of row counts and by

* setting it to Integer.MAX_VALUE, Parquet lib will never perform the check and flush all

* buffered rows to one row group on close(). The same check decides when to flush a rowgroup to

* page. So by disabling it, we are not checking any page limits as well and flushing all

* buffered data of the rowgroup to one page.

*

* <p>TODO: Remove the enforcements of single row group SNOW-738040 and single page (per column)

* SNOW-737331. TODO: Revisit block and page size estimate after limitation (1) is removed

* SNOW-738614 *

*/

return ParquetProperties.builder()

// PARQUET_2_0 uses Encoding.DELTA_BYTE_ARRAY for byte arrays (e.g. SF sb16)

// server side does not support it TODO: SNOW-657238

.withWriterVersion(ParquetProperties.WriterVersion.PARQUET_1_0)

.withValuesWriterFactory(new DefaultV1ValuesWriterFactory())

// the dictionary encoding (Encoding.*_DICTIONARY) is not supported by server side

// scanner yet

.withDictionaryEncoding(false)

.withPageRowCountLimit(Integer.MAX_VALUE)

.withMinRowCountForPageSizeCheck(Integer.MAX_VALUE)

.build();

}

As the comment says, due to an internal limitation on Snowflakes server side, at the moment there is will be one column per page AND there will only be a single row group per Parquet file. This may limit some of the optimizations applied at the Parquet level, i.e. skipping irrelevant row groups, etc. Additionally, due to lack of support of DELTA_BYTE_ARRAY(Delta Strings with incremental encoding), the writer uses V1 of Parquet, which lacks some of the new interesting optimizations introduced in V2, such as RLE encoding, column indexes, dictionary encoding across multiple row groups, etc.

Another aspect of the writer is to control the underlying buffer size for the unflushed rows, which Snowflake want to make efficient:

/*

Internally parquet writer initialises CodecFactory with the configured page size.

We set the page size to the max chunk size that is quite big in general.

CodecFactory allocates a byte buffer of that size on heap during initialisation.

If we use Parquet writer for buffering, there will be one writer per channel on each flush.

The memory will be allocated for each writer at the beginning even if we don't write anything with each writer,

which is the case when we enable parquet writer buffering.

Hence, to avoid huge memory allocations, we have to internally initialise CodecFactory with `ParquetWriter.DEFAULT_PAGE_SIZE` as it usually happens.

To get code access to this internal initialisation, we have to move the BdecParquetWriter class in the parquet.hadoop package.

*/

codecFactory = new CodecFactory(conf, ParquetWriter.DEFAULT_PAGE_SIZE);

The default page size is currently set to 1 MB.

Wrapping Up!

Phew, this has been a lengthy post! if you’ve reached this part, kudos! Snowflake Streaming SDK has many moving parts, and give us interesting insights into some of the details of how Snowflake handles data internally. We always start off with a client, and then create as many channels as needed in order to have sufficient buffers for writing data. After data is written to each channel, we have 3 big operations that are happening:

- Construction of the blobs and their metadata

- Flushing the data to cloud storage

- Registration of files and metadata with Snowflake

Within each one of the operations, we’ve witnessed some interesting properties:

- Serialization using Parquet: the feature has moved from Arrow to using Parquet as the file format for storing the data within Snowflake internal stages before conversion to Snowflakes native FDN format

- Statistics collection: the client collects statistics and ships them to the server side. This could introduce opportunities for query optimization on top of the Parquet files

- Limitations: As the client currently used v1 of Parquet and uses a single row group for all columns, there may be some limitations to the optimizations applied upon querying

As this feature evolves, we’ll probably see more and more optimizations applied to how data is stored internally within the buffers. We’ve seen the evolution from Apache Arrow => Apache Parquet for BDEC files within cloud storage, and the upcoming optimization of storing the internal buffers already in Parquet format in order to reduce the overhead of JVM objects.